I didn’t come to Lesvos as a volunteer. I came as a journalist, to report truthfully what I saw there. But in those crucial, urgent moments – when a few people struggle to feed 2,000 or screaming women hold their infants out to you from a storm-battered boat and there is simply no one else to put out their hands and help, you can’t just stand there and ask for an interview. At least, I couldn’t. So my five days on the island became five weeks. And it was in the act of volunteering whatever support was needed that I found the real story of the refugees: the story of how apathy and mismanagement turned a crisis into a tragedy.

It begins at the beaches. We all know boats are sinking – more than 3,000 lives have been lost this year in the Mediterranean crossing. Just the other day, a boat with 300 people went down. Apart from limited rescue operations by an overstretched Greek coastguard, what I call ‘the Independents’ – small bands of volunteers from Lesvos and around the world – are often all that stand between the refugees and that ugly, growing number.

On my first day on the beaches I was swimming buoyancy aids out to refugees jumping from waterlogged dinghies. That was the day I first used CPR and later, watched as the government registration rules kept a mother from holding her dying child. All this as representatives of a major aid agency stood with dry shoes on the beach taking photos with their phones. The rule, to which I am sure there are exceptions, seems to be that after a day on the beach you can tell the aid workers from the volunteers on the basis of who has wet feet.

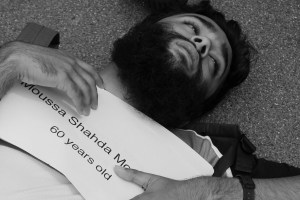

At the island’s makeshift refugee camps, everyone has wet feet. Trench foot and flu were rampant during last week’s storms, and in the absence of adequate shelter construction or even tarpaulin provision, we volunteers handing out bin liners created a frenzy. For weeks, police had been using violence and teargas almost daily. Food shortages have been constant and the near-total absence of translators aggravates regular episodes of panic and violence during the agonising and ineffectual registration system.

Nights are the worst. Once the aid agencies ‘clock off’, there is no one to help the lost child, the bleeding mother-to-be, the ailing grandfather. And in the face of every kind of deprivation you could name, comes a chorus from every corner: “It’s not our jurisdiction.” So the volunteers make it theirs, and even when the world is watching, this is the reality it never sees.

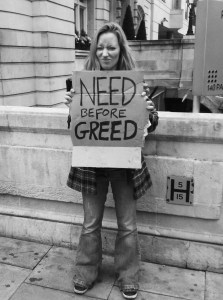

The aid system in Lesvos can and must be reformed. For me, there are three vital elements missing: honesty, humility and humanity.

Honesty

The crisis sweeping Europe is not going away any time soon. Refugee numbers  are on the rise and winter is on the way. Without radical reform, thousands of men, women and children are going to die needlessly on European soil.

are on the rise and winter is on the way. Without radical reform, thousands of men, women and children are going to die needlessly on European soil.

Neither frontline governments nor NGOs can possibly prepare for this unless they are prepared to tell this simple truth.

Perhaps if this were not a debt-ridden nation in the midst of its own crisis, there would be a “gigantic humanitarian effort” under way in Greece, but for the record, there is not. And Camp Moria has not been a place where children get PlayStations and have their faces painted. The racist violence, corruption, police impunity and legal failures criticised in the past are very much still part of the picture. As worrying as this is, the fact is: only the Independents seem willing to speak about them.

Humility

What frustrates the Independents more than anything is the apparent territorialism of the big aid agencies. In one particularly revealing incident, a woman whose infant had drowned on the crossing was literally fought over on the beach by employees of rival charities keen to represent her case and the media attention it would garner. Bartering in this kind of ‘poverty porn’ alienates the refugee community from those who are meant to be supporting them.

Many Independents come with vital skills: lifeguards from Denmark, coastguards from Spain, paramedics from Norway. The list goes on. But often, it’s the basic contributions that are most needed: small-scale fundraising, cooking and cleaning, building shelters and perhaps the most precious commodity of all: time. “You guys are the only ones that make us feel heard,” one refugee told me. Independents also enjoy a degree of freedom that allows them to respond more efficiently to rapidly changing circumstances and endless red tape. We’re prepared to drive hypothermic children to shelter without waiting for police permission, for example. And we are present at all hours in places formal agencies have abandoned.

Most Independents understand that those working for formal organisations, while empowered in some ways, are restricted in others. But when overstretched, the only answer is to collaborate with Independents as autonomous, equal partners in the provision of a lifesaving service; to share resources where possible and maintain a dialogue always.

The same goes for refugees themselves. Many have urgently needed skills – from construction to translation. A formalised and mutually beneficial system to utilise these skills could transform the camps.

Lack of coordination and support leaves untrained Independents working night and day, not getting what they need, while aid agencies seem to have storehouses full of resources and lack the personnel to distribute them. If only an efficient, dynamic relationship could be built between these two sides, we might start to see some of the infrastructure needed to cope with what is surely still to come.

Humanity

Last week, when I needed to get papers fast-tracked for a bereaved mother whose infant was hospitalised and on the brink of death, I asked a UNHCR (UN refugee agency) staff member what could be done for her. He just stared at me. “Please, can you take her name at least? We can have someone look for her tomorrow, make sure she gets where she needs to go,” I implored. He shook his head: “Registration is the police’s responsibility.” I asked him exactly what his responsibility was. He ignored me.

I got my degree in Politics and International Development from SOAS, University of London. When I started, I was aspiring to work for UNHCR myself. What I learned at university made me more critical of the structures in which they operate, but after my experience in Lesvos I really don’t think I ever could. Time and again I’ve been shocked by the apathy and detachment displayed by the professional aid workers. There’s also the question of how Syrians are treated so much better than anyone else, something the aid system doesn’t seem to be contesting nearly enough.

In a crisis situation when most suffer without even the basics, some will always try to cheat the system. It’s not like there would be a level playing field even if they didn’t – the survival game is rigged and competition is brutal. But that doesn’t give anyone, from a position of power and privilege, the right to make generalised assumptions that every starving, dehydrated woman that faints in the queue is faking it or just “hysterical” (a favourite camp term). Once you start making generalised assumptions like that, dehumanising the ones you’re meant to help, you’re no longer qualified to be of help.

***

On the ferry to Athens recently, I hid two Afghan mothers with infants in my cabin so they’d have somewhere to sleep out of the oceanic wind, and spent my evening on deck with some of my new-found Syrian friends. As we talked the night away, we found ourselves cracking jokes about all this, doing impressions, demanding “PAPERS!” from each other whenever someone needed the toilet.

But like me, I think they laugh to keep from crying. Their endurance, their dignity, their courage to carry on, is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen. They’re not victims, they’re survivors. And if my critique of the aid system here seems idealistic, it is only because I hold it to the standards they deserve. The people I have met and the stories they have told me are all the evidence we need: we can do better than this.